Ariadne: Lady of the Labyrinth, the Thread, and Divine Transformation

- Fridrik Leifr

- Sep 15, 2025

- 14 min read

Ariadne, the Princess of Crete, the abandoned lover on Naxos, the wife of the god Dionysus. Her name evokes images of intricate labyrinths, life-saving threads, and a dramatic journey that transports her from mortal despair to divine apotheosis. In the tapestry of Greek mythology, Ariadne is not merely a secondary character in the adventures of male heroes; she is a central figure in her own right, a bridge between the chthonic, earthy world of Minoan Crete and the vibrant Olympian pantheon, a powerful representation of the soul navigating the challenges of life, loss, and transcendence. For modern spiritual seekers, Ariadne offers a rich and multifaceted archetype, guiding them through the complexities of self-knowledge, the healing of emotional wounds, and the celebration of transformation and divine ecstasy.

This article aims to unveil the many veils of Ariadne. We will delve into the mythical narratives that define her trajectory, from her crucial role in the defeat of the Minotaur to her painful abandonment and subsequent union with Dionysus. We will investigate her possible roots as a pre-Hellenic Cretan goddess, the "Lady of the Labyrinth," and analyze the layers of meaning in her most potent symbols: the labyrinth and the thread. We will explore how she may have been perceived or venerated in antiquity and how her figure resonates today, particularly in modern Hellenism and Goddess Spirituality. Finally, we will detail the correspondences—animals, plants, stones, colors, and incenses—that can help us connect with her transformative energy, offering practical ways to honor her and integrate her wisdom into our own lives. Prepare to follow Ariadne's thread through the twists and turns of her fascinating story.

The Mythology of Ariadne: From the Palace of Crete to Divine Union

Ariadne's story is intrinsically linked to some of the most famous figures in Greek mythology and to places laden with mystery and power.

The Princess of Crete and the Minotaur

Ariadne was the daughter of the powerful King Minos of Crete and his wife, Queen Pasiphaë (herself a daughter of the sun-god Helios). Through her mother, Ariadne had divine lineage. Her father, Minos, was the son of Zeus and Europa, further solidifying the family's connection to the gods. However, a shadow loomed over the palace of Knossos: the Minotaur. Due to an offense by Minos against Poseidon (who had sent him a magnificent white bull for sacrifice, which Minos kept for himself), the sea god caused Pasiphaë to fall madly in love with the bull. With the help of the ingenious architect Daedalus, Pasiphaë managed to unite with the animal, resulting in the birth of Asterius, the Minotaur—a creature with the body of a man and the head of a bull, fierce and uncontrollable.

To hide this shame and contain the beast, Minos commissioned Daedalus to build a complex and inescapable structure: the Labyrinth. There, the Minotaur was imprisoned. As a result of a previous war with Athens (in which Minos's son, Androgeus, was killed), Minos imposed a terrible tribute on the city: every nine years (or, in some versions, annually), Athens had to send seven youths and seven maidens to be devoured by the Minotaur in the Labyrinth.

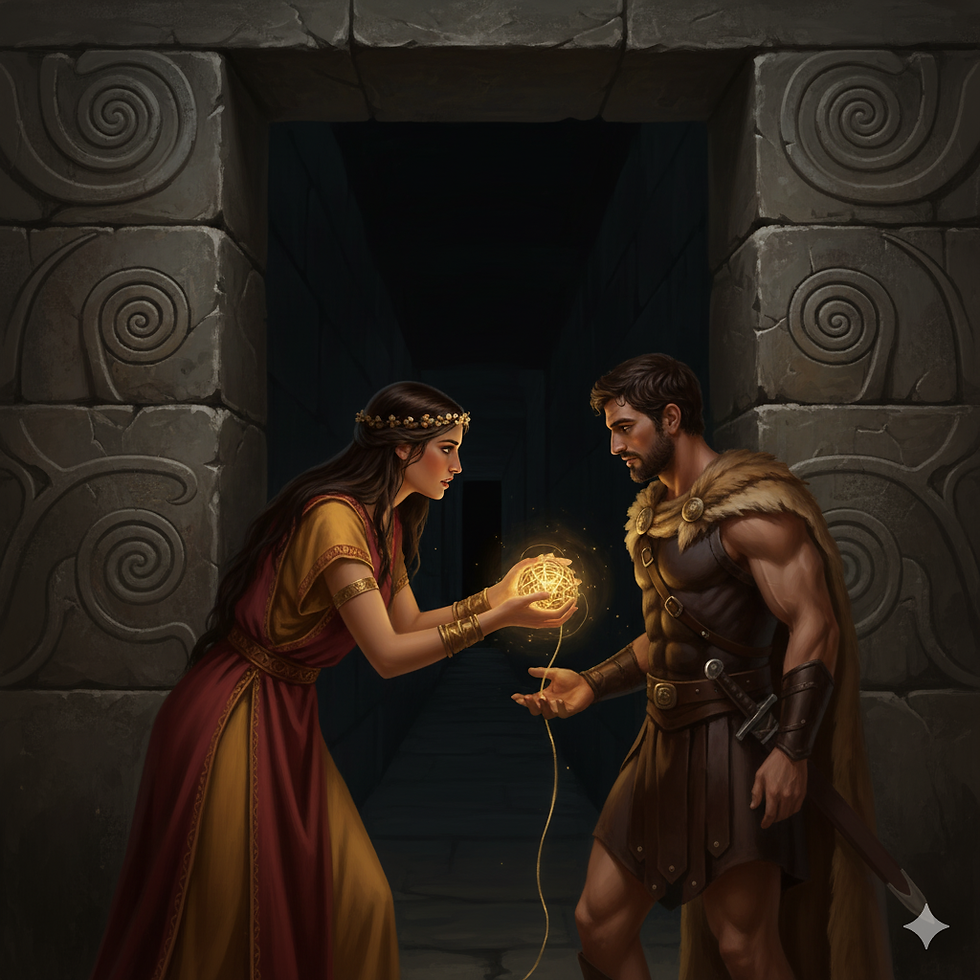

The Arrival of Theseus and the Saving Thread

It is in this context that Theseus, the Athenian hero, son of King Aegeus (or, secretly, of Poseidon), enters the story. Determined to end the gruesome tribute, Theseus volunteers as one of the youths to be sent to Crete. Upon arriving at the court of Minos, Ariadne sees Theseus and instantly falls in love with him (some versions say Aphrodite or Eros intervened). Torn between loyalty to her family and her love for the foreign hero, and perhaps horrified by the fate of the Athenian youths, Ariadne decides to help Theseus.

She seeks out Daedalus (or, in some versions, conceives the idea herself) to find a way for Theseus to survive the Labyrinth. The ingenious solution is a ball of thread (or flax). Ariadne instructs Theseus to tie one end of the thread to the Labyrinth's entrance and to unwind it as he goes deeper. After killing the Minotaur in the center of the structure, he could follow the thread back to the entrance, escaping the deadly trap. In some variants of the myth, instead of a thread, she gives him a shining crown (made by Hephaestus) that illuminates the path in the darkness. In exchange for her vital help, Ariadne makes Theseus promise to take her with him to Athens and marry her.

Theseus agrees. He enters the Labyrinth, unwinds the thread, finds and kills the Minotaur (usually with his bare hands or a sword), and follows the thread back to freedom, rescuing the other Athenian youths as well. Fulfilling part of his promise, Theseus flees Crete with Ariadne (and, in some versions, her younger sister, Phaedra).

The Abandonment on Naxos

The escape from Crete marks the beginning of Ariadne's personal tragedy. The group sails to the island of Dia, later identified as Naxos, the largest of the Cyclades islands and a place strongly associated with the god Dionysus. It is here that one of the most debated acts in Greek mythology occurs: Theseus abandons Ariadne.

The reasons for the abandonment vary greatly depending on the source:

Cruel, Voluntary Abandonment: The most common version, which casts Theseus in a negative light, is that he simply leaves her sleeping on the beach and departs, perhaps because he no longer loved her, feared the reaction of the Athenians to bringing a foreign princess (the daughter of his enemy), or out of pure ingratitude and opportunism.

Divine Intervention (Athena): Some Athenian sources, perhaps trying to justify their hero, claim that the goddess Athena appeared to Theseus in a dream and ordered him to leave Ariadne, as she was destined for another (Dionysus).

Divine Intervention (Dionysus): Another popular version is that Dionysus himself saw Ariadne, desired her for himself, and ordered (or magically induced) Theseus to abandon her. In some variants, Dionysus abducts her while Theseus is away.

Ariadne's Death: A less common tradition, reported by Pausanias citing sources from Argos, suggests that Ariadne died on Naxos, perhaps in childbirth, before Dionysus could find her or Theseus could leave her. Homer, in the Odyssey (Book XI, Odysseus's speech in the underworld), mentions that Artemis killed Ariadne on Dia "because of the testimony of Dionysus," an obscure passage that may imply divine displeasure or a tragic fate.

Regardless of the cause, the result is the same: Ariadne wakes up alone, abandoned, and desperate on an unknown island, watching Theseus's ship disappear over the horizon. This moment of desolation is a favorite theme in classical and later art and literature, symbolizing the pain of betrayal and abandonment.

The Rescue and Union with Dionysus

Ariadne's despair does not last forever. The island of Naxos was sacred to Dionysus, the god of wine, ecstasy, fertility, theater, and transformation. He finds Ariadne (often described as weeping on the beach) and is immediately captivated by her beauty and plight.

Dionysus comforts her and falls in love with her. He takes her as his wife, elevating her from an abandoned mortal princess to the consort of an immortal god. This union is often depicted as joyful and triumphant, a direct contrast to her abandonment by Theseus. Dionysus offers Ariadne immortality or a divine status. As a wedding gift, he gives her a magnificent crown (the same one she gave Theseus in some versions, or a new one), studded with jewels or stars. Later, to immortalize his love and her beauty, Dionysus casts this crown into the heavens, where it becomes the constellation Corona Borealis (the Northern Crown).

With Dionysus, Ariadne had several children, including Oenopion (associated with wine), Staphylus (associated with grapes), Thoas, Peparethus, and others, who often became kings or important figures on different Greek islands, spreading Dionysian influence. The union of Ariadne and Dionysus represents the integration of human suffering with divine ecstasy, the transformation of pain into celebration, and the elevation of the soul through divine love and initiation.

Interpretations and Divine Status: More than a Princess?

Interpretations and Divine Status: More than a Princess?

The figure of Ariadne raises fascinating questions about her original status and her evolution within Greek mythology.

Possible Cretan Goddess: Many scholars suggest that Ariadne may have originally been an important goddess of Minoan Crete, perhaps associated with fertility, vegetation, the underworld, or weaving, who was later "humanized" and incorporated into Hellenic narratives centered on male heroes like Theseus. Her name, sometimes interpreted as "Ariagne" (derived from ari - very, and hagnos - holy, pure), suggests a divine status: "Most Holy." The Minoan culture had a central female divine figure, often depicted with snakes, on mountain peaks, or associated with trees and animals (especially the bull), and Ariadne could be a late reflection of this tradition.

Lady of the Labyrinth: The Labyrinth was not just a prison for the Minotaur but a potent symbol in Minoan Crete, possibly linked to initiation rituals, sacred dances, or the palace of Knossos itself. If Ariadne was the one who held the key (the thread) to navigate its center and return, this positions her as the "Lady" or guide of the Labyrinth, a figure of power and initiatory knowledge, not just a lovesick maiden. The labyrinth can represent the soul's journey, the unconscious, or the path to the divine, and Ariadne would be the psychopomp or initiator. The dance that Daedalus was said to have taught Ariadne (mentioned in the Iliad) may have been a ritualistic labyrinthine dance.

Deification by Dionysus: Even if considered a mortal by birth, her union with Dionysus elevates her to a divine or semi-divine status. As the wife of a major Olympian god, she partakes in his immortality and power. The placement of her crown as a constellation is a clear act of catasterism (transformation into a star), a sign of divine honor. She becomes part of Dionysus's thiasos (retinue), participating in his mysteries and celebrations. In some Orphic or mystery traditions, Ariadne may have had an even more significant role alongside Dionysus, perhaps linked to the cycles of death and rebirth.

Therefore, viewing Ariadne merely as a betrayed princess is to reduce her complexity. She represents the interface between the human and the divine, the mortal and the immortal, suffering and ecstasy.

Mythological Correlations

Ariadne's story echoes and connects with other mythological figures and themes:

Dionysus: Her most important correlation. She becomes the feminine complement to the god of ecstasy, divine madness, and liberation. While he represents the wild transformative power, she may represent the soul undergoing that transformation.

Persephone: Both are female figures linked to powerful gods (Dionysus and Hades) who take them to their realms (divine ecstasy and the underworld, respectively). Both undergo a form of "death" (abandonment/descent) and "rebirth" (divine union/return to the surface).

Theseus: Represents the solar, rational hero focused on action and earthly (Athenian) glory. His abandonment of Ariadne may symbolize the inability of this archetype to fully integrate the deep feminine, mystery, or the chthonic divine that Ariadne represents.

The Minotaur: Her monstrous half-brother, represents bestial nature, repressed instinct, or the "other" that must be confronted at the center of the labyrinth (the center of the self). Ariadne, by providing the means to defeat and escape him, facilitates the integration or overcoming of this shadow.

Daedalus: The ingenious architect, represents technical intelligence and creation, but his inventions (the Labyrinth, Icarus's wings) often lead to complex or tragic consequences. He is a key enabler in Ariadne's story.

Weaver Figures: While not primarily a weaver like Athena or the Fates (Moirai), her thread symbolically connects her to the act of weaving destiny, finding one's path, and connecting different points of the journey.

Ancient Cult: Traces and Possibilities

Direct evidence of a formal cult to Ariadne as a major goddess in classical mainland Greece is scarce. However, there are clues and possibilities:

Cult on Naxos: The island where she was abandoned and rescued by Dionysus was a major center of Dionysian worship. Pausanias mentions two distinct traditions about Ariadne on Naxos, suggesting a significant local presence. It is likely she was honored there, perhaps in conjunction with Dionysus, in festivals celebrating the grape harvest, fertility, and perhaps the mysteries of transformation. Some rituals could have reenacted her suffering and her divine salvation.

Cult on Crete: If she was a Minoan goddess, traces of her worship may be subsumed in later rituals or the veneration of other deities. The importance of female figures in Minoan art and religion is undeniable, and Ariadne may have been one of them. Labyrinthine dances, possibly performed on Crete, could have been linked to her.

Festivals: Some Greek festivals, such as the Oschophoria in Athens (which involved grapevines and was linked to Theseus and possibly Dionysus and Ariadne), might have contained elements related to her story.

Heroine or Nymph: It is possible that in some places she was venerated more as a local heroine or a nymph associated with Dionysus, rather than a full Olympian goddess.

The lack of prominent temples or inscriptions may be due to her more chthonic or mystery-oriented nature (if linked to Dionysus and Minoan rituals), or the fact that the dominant Athenian narratives relegated her to a more human role.

Ariadne in Modernity: Guide, Healer, Goddess of Transformation

In modern times, Ariadne has re-emerged as a significant figure in various spiritual currents, especially those focused on the divine feminine and the reconstruction of ancient pantheons.

Modern Hellenism: Within Hellenism (the modern reconstruction of ancient Greek religion), Ariadne is often honored as the divine wife of Dionysus. She may be seen as a goddess of passion, loyalty (despite Theseus's betrayal), compassion (for helping Theseus and the Athenians), and transformation through suffering. Devotees may invoke her alongside Dionysus, especially in rituals related to wine, dance, theater, or the celebration of life's cycles.

Goddess Spirituality and Wicca: Here, Ariadne is often embraced as a powerful archetype of the female soul's journey.

Guide in the Inner Labyrinth: She is the Lady of the Labyrinth, the one who holds the thread that guides us through the complexities of our unconscious, our fears, and our shadows (the inner Minotaur). She is invoked for self-knowledge, for finding the way in times of confusion, and for integrating shadow aspects of ourselves.

Overcoming Abandonment and Betrayal: Her story of abandonment on Naxos resonates deeply with those who have experienced betrayal, loss, or loneliness. She becomes a symbol of resilience, the ability to find salvation and transformation even at the lowest point, and the healing of deep emotional wounds.

Transformation and Rebirth: Her journey from mortal princess to divine consort is a powerful symbol of transformation and rebirth. She represents the soul's alchemy that turns suffering into ecstasy and human limitation into divine potential.

Connection to Creativity and Destiny: Ariadne's thread is also seen as a symbol of the weaving of life and destiny, connecting her to creativity, manifestation, and the conscious navigation of life's choices.

Archetypal Psychology: Jungian and other psychologists may use Ariadne's story to explore complexes related to the feminine, the relationship with the masculine (animus), betrayal, and individuation (the journey through the labyrinth of the self).

Ariadne today is seen as a compassionate, wise, and powerful goddess or guide who understands human pain but also points to the possibility of redemption, ecstasy, and union with the divine.

Magical and Natural Associations of Ariadne

To connect with Ariadne's energy, we can work with her symbols and correspondences:

Symbols:

Labyrinth/Spiral: Her most potent symbol. Represents the inner journey, the unconscious, the path to the center (of the self, of the divine), initiation, death, and rebirth. Used in meditation (finger labyrinths, visualizations) or as altar decor.

Thread (Clew): Symbol of guidance, connection, memory, problem-solving, the way back to safety or consciousness. Can be used in knot magic, ritual weaving, or as a reminder to follow one's intuition.

Crown (Diadem): Represents her royalty (earthly and divine), her union with Dionysus, the reward for her ordeal, and immortality (Corona Borealis). A symbol of divine status and achievement.

Grapes and Vine: Direct link to Dionysus and Naxos. Symbolize ecstasy, transformation, abundance, celebration, and the Dionysian mysteries.

Mask: Associated with Dionysus and theater, represents transformation, concealment and revelation, and the different roles we play.

Ship: A symbol of journey, transition, but also of abandonment and departure in her story.

Animals:

Panther/Leopard: Strongly associated with Dionysus and his retinue. Represent sensuality, wild power, mystery, and the untamed nature that Ariadne embraces through her union with the god.

Bull: Connection to Crete, the Minotaur, and Minos. Represents raw strength, fertility, the shadow/instinctual side that must be confronted (Minotaur), but also royalty and power (Minoan bull cult).

Serpent/Snake: Possible link to Minoan goddesses of the earth and fertility. A symbol of rebirth, chthonic wisdom, healing, and transformation.

Spider: Though not directly in the myth, her connection to the thread symbolically links her to the spider as a weaver of destiny and a creator.

Colors:

Red: The color of the thread in many depictions, symbolizing passion, life, danger, blood, courage.

White/Silver: Initial purity, lunar connection (if seen as a goddess), clarity of the thread, the stars of Corona Borealis.

Gold: Royalty, divinity, the crown, the sun (lineage from Helios), achieved divine status.

Purple/Wine: The color of Dionysus, royalty, mystery, ecstasy, spiritual transformation.

Black: The darkness of the Labyrinth, the unconscious, the underworld (themes of transformation), the night of abandonment.

Green: Connection to Dionysus as a god of vegetation, fertility, rebirth (especially vines).

Herbs and Plants:

Grapevine (Vitis vinifera): The quintessential plant of Dionysus. Used to honor their union and the gifts of ecstasy and transformation. Leaves and grapes can decorate the altar.

Ivy (Hedera helix): Another plant sacred to Dionysus, symbolizing resilience, immortality (evergreen), and ecstasy. Used with caution (some parts are toxic).

Fig Tree (Ficus carica): Associated with fertility and Dionysus.

Flax (Linum usitatissimum): The plant from which the thread could be made. Represents connection, weaving, destiny.

Saffron (Crocus sativus): An important flower in Minoan art, possibly linked to female rituals and goddesses. Vibrant color (yellow/red).

Dittany of Crete (Origanum dictamnus): An herb native to Crete, known for healing and magical properties. Can be used to honor her Cretan roots.

Stones and Crystals:

Garnet (especially red): Its color can echo the thread. Associated with passion, life force, protection on the journey (labyrinth), and overcoming crises.

Amethyst: The stone of Dionysus, linked to sobriety amidst ecstasy, spiritual transformation, calm, and connection to the divine.

Rose Quartz: For healing a broken heart (abandonment), self-love, compassion (for oneself and others).

Lapis Lazuli: Deep blue color with golden pyrite, evokes the starry sky (Corona Borealis) and royalty. Associated with wisdom and inner truth.

Clear Quartz: Clarity for navigating the labyrinth, amplification of intention, connection to the thread of consciousness.

Obsidian or Black Tourmaline: For shadow work, protection on the inner journey (labyrinth), grounding.

Moonstone: Connection to the divine feminine, intuition, cycles of transformation.

Incenses:

Frankincense: Purification, spiritual elevation, connection to the divine (her deified nature).

Myrrh: Associated with healing, the underworld (journey through the labyrinth), and overcoming suffering.

Dragon's Blood: A red resin, linked to strength, passion, protection, and empowering rituals. Echoes the color of the thread.

Storax: An incense traditionally associated with Dionysus and ecstatic rituals.

Rose: For emotional healing, love (divine and human), compassion.

Sandalwood: Meditation, spiritual connection, calms the mind for the inner journey.

Cedarwood: Strength, resilience, connection to ancient wisdom (her Minoan roots).

Utilizing the Associations in Modern Worship

Integrating these elements can enrich devotional or magical practice with Ariadne:

Dedicated Altar: Use colors like red, purple, gold, or white. Include images or symbols of Ariadne, Dionysus (if you wish to honor the union), labyrinths, threads, crowns, panthers, or bulls. Arrange stones like Amethyst, Garnet, and Rose Quartz. Offer wine, grape juice, grapes, figs, or bread. Burn incenses like Frankincense, Myrrh, or Storax.

Labyrinth Meditation: Use a finger labyrinth (printed or drawn) or visualize one. Ask Ariadne to guide your inner journey as you trace the path to the center and back. Use the center for introspection, confronting shadows, or seeking clarity.

Thread Magic: Use a red thread (or another significant color) in rituals. Wrap it around a candle while meditating on a problem, asking Ariadne for a solution or a clear path. Use it to create sigils, intention bracelets, or in binding/unbinding spells.

Devotional Dance: Play music that evokes mystery, ecstasy, or transformation. Dance freely, allowing your body to express Ariadne's journey—the tension, the love, the abandonment, the pain, the rescue, the ecstasy. Dedicate the dance to her and Dionysus.

Emotional Healing Work: If dealing with feelings of abandonment, betrayal, or loss, create a simple ritual for Ariadne. Light a candle (perhaps pink or purple), hold a Rose Quartz, and ask for her help to navigate the pain and find strength and transformation, just as she did. Write about your feelings and then safely burn the paper as an act of release.

Honoring the Divine Union: Celebrate the union of Ariadne and Dionysus with a small feast, offering wine or grape juice, fruits, and bread. Read poetry or hymns dedicated to them. Reflect on how ecstasy and transformation can arise even after periods of hardship.

Remember that personal connection is key. Use the associations that resonate with you and adapt the practices to your own intuition and spiritual path.

Conclusion: The Eternal Thread of Ariadne

Ariadne is a figure of enduring resonance, a goddess whose journey mirrors the complexities of the human and spiritual experience. From the princess who defied her father for love to the abandoned soul on a deserted beach, and finally to the divine consort celebrating alongside Dionysus, her story is a powerful narrative of transformation. She is the Lady of the Labyrinth, not just of the physical structure in Crete, but of the inner labyrinth we all must navigate to find our center, confront our inner monsters, and emerge with greater self-awareness.

Her thread is not just a trick to fool a maze, but a symbol of intuition, ancestral wisdom, the connection that guides us through darkness and confusion. It is the thread of memory, the thread of destiny, the thread that links us to the divine even when we feel lost or disconnected. The abandonment she suffered, though painful, became the catalyst for her greatest glory, teaching that even in moments of deepest despair, an unexpected transformation and a divine union may be waiting.

For those who feel lost in their own personal labyrinths, who face the pain of betrayal or abandonment, or who seek a deeper connection with ecstasy and divine transformation, Ariadne offers her compassionate presence and her guiding thread. She reminds us that every twist and turn of the path has a purpose, and that at the center of our being lies not a monster to be feared, but a divine potential waiting to be discovered and celebrated. May we have the courage to follow the thread, face our challenges, and dance to the rhythm of transformation, guided by the Lady of the Labyrinth, Ariadne.

$50

Product Title

Product Details goes here with the simple product description and more information can be seen by clicking the see more button. Product Details goes here with the simple product description and more information can be seen by clicking the see more button

$50

Product Title

Product Details goes here with the simple product description and more information can be seen by clicking the see more button. Product Details goes here with the simple product description and more information can be seen by clicking the see more button.

$50

Product Title

Product Details goes here with the simple product description and more information can be seen by clicking the see more button. Product Details goes here with the simple product description and more information can be seen by clicking the see more button.

Comments